So, as most of my real-life friends know, I’m half-Puerto Rican. I’m a first-generation mainlander one parent’s side. (This is a little different than being a first-generation American; the parent in question was born an American, as were my grandparents, but I am the first to be born off the island.) My Spanish ancestors went to Puerto Rico in the early 1800s. My family has been active in Puerto Rican politics for years, too; we have streets all over the island named for various family members.

Background

A little background on Puerto Rico first. Puerto Rico was “discovered” (despite the native Taino having lived there forever) by Columbus on his second trip to the new world. It was a territory/province of Spain up until the beginning of the 20th century. In 1898, the United States invaded the island during the Spanish-American War. Although the US retained control of Puerto Rico for the next two decades, the people living there (including my great-grandparents) were all Spanish citizens. In 1917, the Jones Act passed and all Puerto Ricans were made United States citizens. People on the island went to sleep citizens of one country and woke up citizens of another thanks to Teddy Roosevelt. In the early 1950s, there were revolts, votes, and a referendum to establish Puerto Rico as a commonwealth and unincorporated territory of the United States and have its own constitution.

Puerto Ricans are American Citizens. They do not have a representative in Congress, but they also do not pay federal income tax. They do pay into Social Security but not Supplemental Security Income (SSI). They lack full protection of the U.S. Constitution. They cannot vote for President (although they can vote in the primaries). They cannot deal directly with other nations. They are part of the First Federal Circuit of the United States Judiciary. They receive a small percentage of the Medicaid funding they would receive otherwise. They also suffer from an abnormally high unemployment rate (reports vary, but seem to hover around 16-18%). Crime, as a result, is up. Poverty is obviously up. Puerto Rico is generally treated as a state by government agencies (such as FEMA or the EPA).

Puerto Rico has had many referendum votes over the years about whether or not to join the United States, so when I heard it was back up for a vote again this year, I only sort-of followed the process (mainly via my cousins’ posts on Facebook). But then, I learned that they were doing something a little different this time around: a two-part referendum. In 2010, the U.S. House voted to give Puerto Rico a federally-supported process for self-determination. This measure also said that Puerto Rico could revisit the issue every eight years (or two presidential election cycles) if they chose to maintain the status quo. The Senate killed the bill without voting on it. The Puerto Rican Congress instead moved forward with their own decision to offer up the referendem anyway.

In the past, the votes have been either for statehood or independence. That is, they were either voting to stay a territory or become a state, OR (in separate votes) to become an independent country or remain a territory. The votes always came out to maintain the status quo as a US territory – people wanted a change, but couldn’t agree on what change, so the vote would stagnate.

The Referendum

This time, the referendum asked two questions.

- Should we maintain the status quo?

- If we make a change, what change should we make?

- Statehood

- Sovereign Free Associate State

- Independence

You did not have to vote to make a change to still get a say in the second part – in other words, you could say “No, I don’t want a change… but if we do change this is what I want.”

This created a huge difference in results.

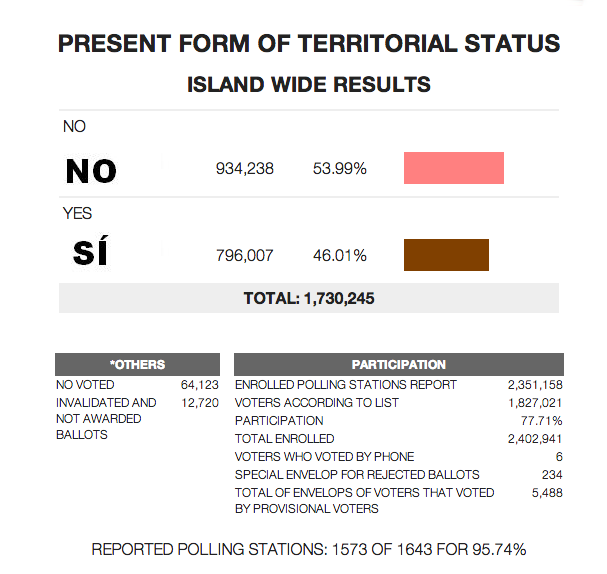

Just to make sure I’m clear here: the question was whether to maintain the status quo. This means a “no” is a vote for a status change. A “yes” was to keep on with no change.

A 54%-46% split may not seem like a huge change, but since, historically, it’s been 46% for Statehood (instead of against), that eight percent jump is pretty big. It’s also important to note that nearly 80% of the registered votes came out to have their say, so this is a good representation of the peoples’ voices.

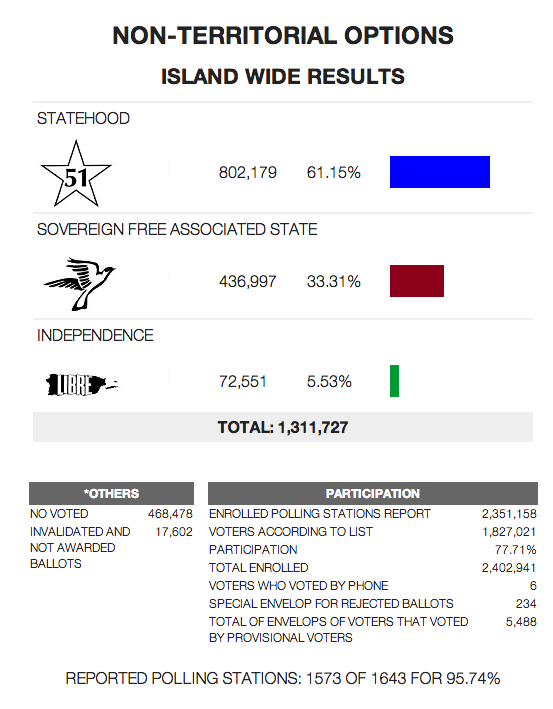

And then there’s the breakdown of question two:

Again – this is not a percentage of the 54% who said, “Let’s make a change.” This is of the full group of voters, whether they support a change or not.

61% would make Puerto Rico a state. That is nearly 2/3 of the island that would support becoming the 51st state if they make a change.

What Now?

Well, the referendum was non-binding, which means Puerto Rico doesn’t have to become a state because of this. However, it does mean the results can be brought to Congress, which can then vote. This is done under Article IV, Section 3 of the U.S. Constitution. They don’t need to do an Enabling Act, as Puerto Rico already has a constitution. Congress also doesn’t need a 2/3 majority vote – a simple majority vote could bring Puerto Rico into the United States.

It’s been more than 50 years since Alaska and Hawai’i joined the United States of America. It would be amazing to see Puerto Rico finally brought into the fold.

And for those curious about what the flag would look like:

Election Results taken from CEEPUR.org.